As we kick off our fifth year in India, I knew it was time to stop avoiding Varanasi.

A key destination for any serious tourist to the subcontinent, this North Indian city dedicated to the god Shiva is also a place of holy pilgrimage for Hindus. They believe a bath in the sacred Ganges River will purify them, and moksha – a kind of salvation or liberation from the cycle of life – comes to those who die here. In fact, the elderly move to state-subsidized ashrams in Varanasi to wait out the last months or years of their lives, walking down the steep steps to the Ganges each day for a sin-absolving dip. The dead burn on funeral pyres along the shore, their ashes swept into the river.

It all sounded a little overwhelming, and frankly, when holidays roll around in New Delhi, I feel the need to escape the chaos. However, we don’t know how much longer we’ll live in India, and there are significant locations I don’t want to miss. Invited to join a group traveling to Varanasi last weekend, I knew it was time to check out one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world.

After a short flight and about an hour in a van, our group of eight teachers reached the Ganges River in Varanasi Saturday afternoon.

We piled into a wooden motor boat and put-putted upstream to our hotel, Suryauday Haveli.

I tried to find some historical information about this beautiful riverfront structure, but every website parrots the blurb on the hotel’s home page (Benaras is another name for Varanasi):

Suryauday Haveli on Shivala Ghats is a reflection of the spirit of the holy city of Benaras. The Haveli traces its history back to the early 20th century. It was built by the Royal Family of Nepal as a retreat for the aged. It’s now been painstakingly put together again to provide the best ghat experience in Benaras.

Ghat refers to the series of steps that lead from the building to the water. Suryauday Haveli is located at Shivala Ghat, which fortunately (and unlike many other ghats), didn’t have too many stairs. It did, however, feature a little herd of waterbuffalo cooling off ears-deep in the holy water. The hotel staff welcomed us with a shower of rose petals from the balcony.

Our rooms all faced the river and opened to a courtyard shaded by trees and decorated with marigold blossoms.

Here’s Sarah, my roomie for the weekend.

After awhile, we met up with former AES teacher, Jill, who started Lotus Foundation here to provide education, health care and job training to children and young adults from the Varanasi slums. On the way to see her school and hostel, we stopped to meet some of the children who benefit. As soon as we climbed out of the auto rickshaws at the banks of the Ganges, children and their mothers approached to meet the strangers and chat with Jill. The little ones immediately engaged us in jumping and clapping, despite the language barrier. We snapped photos and showed them the images, which triggered hysterical giggling. We also visited Jill’s humble school, where up to 20 students receive a free education, and her small hostel, where a few young girls can sleep safely. Her foundation is presently busy with renovations as they prepare to open a guesthouse and restaurant, offering job training to people living in poverty.

Marina plays a clapping game with Radha.

Jill shares a laugh with little Veer.

Showing my photos to the kids was hilarious.

Posing in front of Jill’s school.

The playroom. Kids do most of their learning in another room, sitting on mats.

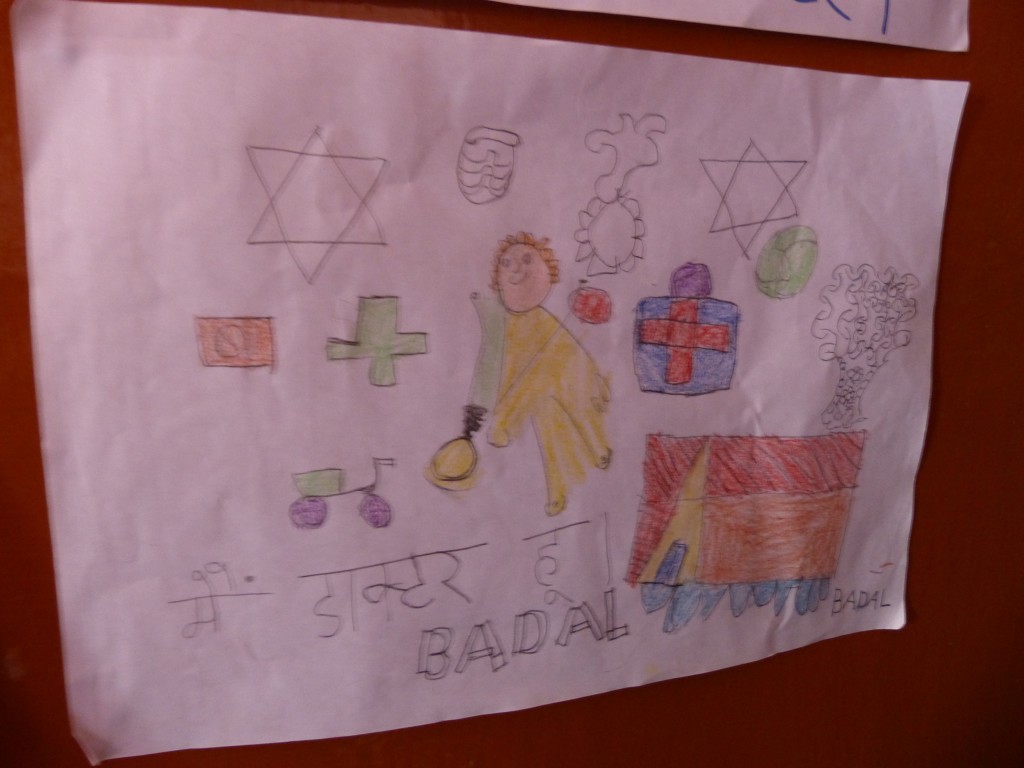

Badal wrote in Hindi, “I am a doctor.”

At sunset, our hotel offered a complimentary boat ride to see the ceremony at the Dashashwamedh Ghat, the main and most lively ghat on the river. The shore was already crowded with boats when we arrived, so we pulled up alongside them and waited for the ceremony. The nightly aarti – which honors the river goddess – features blowing of a conch shell, incense burning, waving lamps of fire, bell ringing, clapping and chanting. Although we really couldn’t see the action, I always love the energy of people at a religious pilgrimage site, and I often found myself facing the crowd to see their reaction to the aarti. Eventually, our guide, Sanjay, told us to light our offering and drop it into the water. I had hoped to see hundreds of candles floating on the Ganges, but the current quickly swept them away.

The next morning, a few of us met Sanjay again at 5 a.m. for a sunrise cruise. We slowly motored along the quiet shoreline to the Manikarnika Ghat. Although a body lay in wait on the ghat steps, the workers were mainly cleaning up from the previous day, sweeping, stacking wood, sorting through ashes.

According to Lonely Planet,

Manikarnika Ghat, the main burning ghat, is the most auspicious place for a Hindu to be cremated. Dead bodies are handled by outcasts known as doms, and are carried through the alleyways of the old city to the holy Ganges on a bamboo stretcher swathed in cloth. The corpse is doused in the Ganges prior to cremation. Huge piles of firewood are stacked along the top of the ghat; every log is carefully weighed on giant scales so that the price of cremation can be calculated. Each type of wood has its own price, sandalwood being the most expensive. There is an art to using just enough wood to completely incinerate a corpse. You can watch cremations but always show reverence by behaving respectfully.

The early birds were already starting to show up at the bathing ghats.

Stacks of wood fill the building and line the steps at Manikarnika Ghat.

Workers unload wood from a boat.

Boating back to our hotel, we watched the riverbanks come to life. Bathers soaped up their bodies, young men gleefully flipped into the water, and elderly couples stood chin deep while chanting. Ladies in colorful saris ladled water over their babies. Dhobis beat their river-washed laundry on the ghat steps and then put it out to dry in the relentless sun, spread on the steep stone hillsides or hung from railings. Small fires burned at the Harishchandra Ghat, a secondary cremation center near our hotel.

18-year-old Sanjay pilots the boat and shares stories about Varanasi.

White sheets spread out on the brick walls were “hospital laundry,” Sanjay said.

It’s no small feat to keep the monkeys off your clean sheets!

After an extended breakfast (with delicious coffee, courtesy of Maureen’s Miracle Coffee Maker), our group headed out for a walk along the river.

More laundry. I just loved it.

A little slice of life at Dashashwamedh Ghat. I was sweating my face off, but those ladies look remarkably cool in their saris.

Sarah and I broke off from the group to check out the Kedareswara Temple, a squat red-and-white striped structure at the top of a long flight of alternating red- and white-painted stairs. I read conflicting and confusing stories about this temple’s history, but here’s one version from the webindia123 website, with a few edits:

Kedareshvara alias Kedareshwar temple, dedicated to Lord Shiva is a river temple situated right on the banks of the Ganga at the top of Kedar Ghat. The stone Shiva lingam is said to have appeared spontaneously and a visit to this temple is believed to give one the fruits of a visit to the great Kedareshvara Temple at Himalayas. Legends has it that a pure hearted devotee of Lord Shiva prayed for a chance to visit the famous Kedareshvara temple in the Himalayas. Pleased by the devotion, instead of bringing him to the mountain, the Lord brought his lingam which is emerged out of a plate of rice and lentils, to the devotee. It is this lingam that can be seen on the rough surface of the natural stone.

The remains of temple offerings. This was the only photo I snapped before I was scolded, “No camera!”

By the time we met up again with the rest of our group at the Man Mahal Palace, we were all soaked in sweat and completely exhausted, depleted by temperatures hovering around 100F and relative humidity at 87 percent.

The palace was built around 1600 by Raja Man Singh, the king of Amber. More than 100 years later, Sawai Jai Singh II added on to the palace’s masonry observatory. According to The Archaeological Survey of India, Sawai Jai Singh II, a great astronomer and founder of the city of Jaipur, installed “instruments for calculating time, preparing lunar and solar calendars and studying the movements, distances, and angles of inclination of the stars, planets and other heavenly bodies.”

We lingered in the palace’s cross breezes, checking out photography exhibits and information about the astronomical observatory. Mark actually lay down on the cool stone floor to watch a looping TV video about the Ganges River.

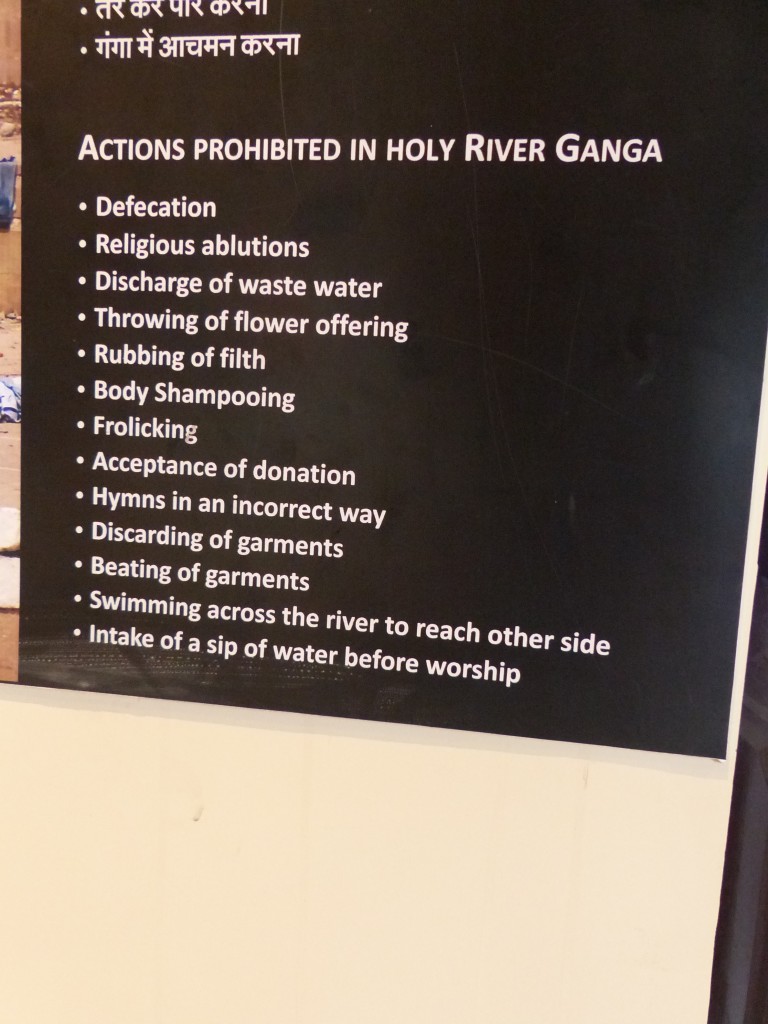

This sign was part of a Ganges River exhibit in the palace. During our walks and boat rides, we witnessed many of these “prohibited actions.” As Jill said, there’s little hope for the river as long as the city continues to pump it full of sewage, so these unenforced rules hardly matter. Read more in this bleak article from Down to Earth.

Finally, we prepared to leave, and Craig asked a worker how to find the Thatheri Market.

“Up,” the guy answered, gesturing toward some steps.

“We just go up the street?” we probed.

“No, upstairs,” he said. “Observatory.”

Oh, yeah! The whole reason we had paid the Rps 100 ($1.50) admission fee! Clearly, we were dehydrated and not thinking straight.

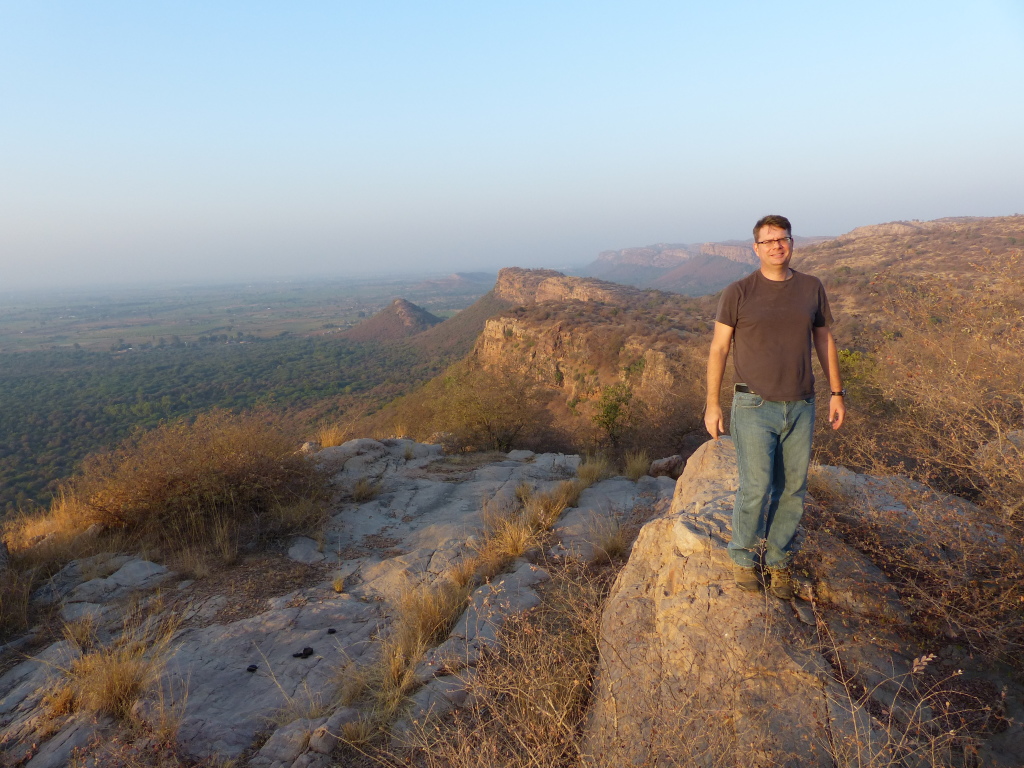

We climbed the steps to the observatory and checked out the hulking instruments and the fantastic views. (The sun dial’s time was just one minute off from Craig’s phone. Amazing.) This site is one of five masonry observatories constructed by Sawai Jai Singh II, including one in Delhi. They are known as Jantar Mantar, which ASI says is “a corrupt form of Yantra-Mantra, meaning the calculation with the help of instruments.”

(Tony and I visited the Delhi Jantar Mantar a couple years ago. You can read about it here: Celebrating 20 Years With an Imperial Anniversary.)

Views from the palace rooftop.

Posing with the sun dial and the samrat yantra – aka “the supreme instrument” or, as we dubbed it, “stairs to nowhere.” The samrat yantra was an instrument for telling time and the coordinates of celestial objects.

We climbed around the observatory for awhile and then checked out the nearby market area. After watching this cow steal a potato from a vendor and after searching in vain for a Varanasi magnet for Craig, we took bicycle rickshaws back to our hotel and ordered both Dominos pizza and room service for a huge lunch banquet in Maureen’s room.

Jill met us again later for another aarti. This time, we visited Assi Ghat and watched the ceremony from the shore, sitting on the stone steps close to the action.

Overall, I found the hype about Varanasi to be mostly unfounded.

True, the river was distressingly polluted. But the pilgrims who stepped or leapt into its murky water believed at that moment that it was pure and powerful. We couldn’t help but feel their visceral joy.

True, the weather was oppressive. But we returned each day to a historic hotel with air conditioning, water pressure and dry clothes. Just another reminder of how fortunate we were.

True, there was no avoiding the reality of death (both human and bovine, it turned out). But those who watched their loved ones burn at the river’s edge didn’t cry. In their eyes, this event was a gift: death had brought salvation through the glory of the holy Ganges. That’s a pretty powerful experience to witness. (I don’t know if the same rules applied for the dead water buffalo.)

With so many more adventures to be had in India, I am unlikely to re-visit Varanasi. However, I can honestly say it is a special place, not to be missed.