Go back in time about 2,200 years.

That’s what I did with a few friends for Thanksgiving. After an early morning flight to Aurangabad and a quick breakfast at our hotel, we were on the road to the Ajanta Caves by 9 a.m. with our guide, Rahman.

So, if you go back in time to around the 2nd century BC … you might pause while fishing in the Waghora River to gaze up at the horseshoe-shaped cliff that hugged your nook of the Deccan Plateau. Maybe you would take a deep breath and feel grateful for the towering volcanic basalt walls enclosing your idyllic spot in west-central India. Then, maybe someone would tap you on the shoulder and said, “Hey, you know how Buddhism is really popular right now? Well, the king wants us to carve some caves into those cliffs for the Buddhist monks to chillax and study during monsoon season. So, I’m thinking you hold the chisel in place, and I’ll whack it with a sledgehammer.”

And so it began. (maybe…)

Ajanta Caves

Between 200 BC and 150 AD (thereabouts), workers dug into the hillsides to create caves where the monks could live, study and worship. Some were simple caves with small living quarters and rock beds. Some caves featured stupas, symbolic mound-like structures that were carved out of the solid rock as the space was excavated. Buddhists of that era revered the stupa, which was topped by a shelf for Buddhist relics (an eyelash here, a fingernail there). Cave construction took a hiatus for awhile, but resumed in the 5th century. By then, Buddhism had entered a new phase that included worshipping images of Buddha himself at all stages of his life and in all sorts of symbolic postures. However, soon Hinduism gripped the region, and the caves lost their appeal to everyone but local goatherds. Forgotten by the outside world for more than 1,000 years, they were lucky to escape the medieval Muslim invaders, who decimated many of the region’s other sacred sites.

Why were the caves carved HERE? According to Lonely Planet:

Located close enough to the major trans-Deccan trade routes to ensure a steady supply of alms, yet far enough from civilization to preserve the peace and tranquility necessary for meditation and prayer, Ajanta was an ideal location for the region’s itinerant Buddhist monks to found their first permanent monasteries. … In its heyday, Ajanta sheltered more than 200 monks, as well as a sizable community of painters, sculptors and labourers employed in excavating and decorating the cells and santuaries.

Eventually, a British soldier on a hunting expedition spotted one of the caves from a hilltop. He started the unfortunate tradition of scratching his name and date into the ancient cave paintings – John Smith, 1819. Tourists now throng to these caves, which are slowly deteriorating. While security guards and tour guides can help deter graffiti artists, there’s no stopping Mother Nature and her annual monsoon assault. Rainwater seeps through the porous rock, collecting in buckets as it drips from finely painted ceilings.

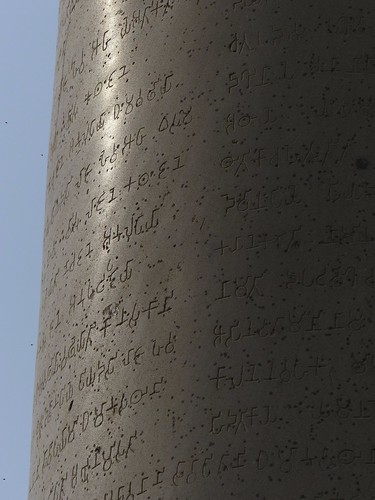

The UNESCO World Heritage site features 29 caves lining a modern-day sidewalk. Their very existence would be fascinating enough, but the cave walls host surprisingly preserved paintings revealing influences from China, Greece, Egypt, Persia and other parts of the world. Murals tell stories from Buddhist (and later, Hindu) mythology, battles, local history and everyday life.

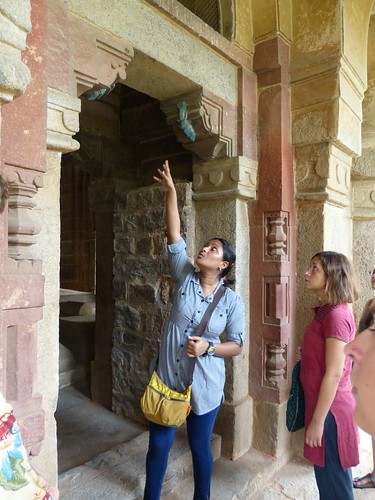

Rahman led us to the oldest caves first. He pointed out windows and arches sculpted in the shape of a peepal tree leaf. Buddha found enlightenment under the peepal tree, also known as a bodhi tree, so its distinctive leaf is both lovely and symbolic. Here’s a peepal leaf-shaped lintel over the door to a monk’s simple bedroom.

Cave 9 dates from the 1st century BC but has some paintings that were added 600 years later. Its vaulted ceiling was originally braced with superfluous wooden beams and rafters.

In Cave 10, we saw John Smith’s scrawl (which was hard to photograph in the dim light)…

… as well as some stunning paintings.

Marina, Kathryn, Lloyd, me and Nancy striking some of Buddha’s famous postures.

After introducing us to a few caves, Rahman set us free for awhile.

This elderly lady opted for a ride with the “dhooli-wallahs” (sedan-chair porters).

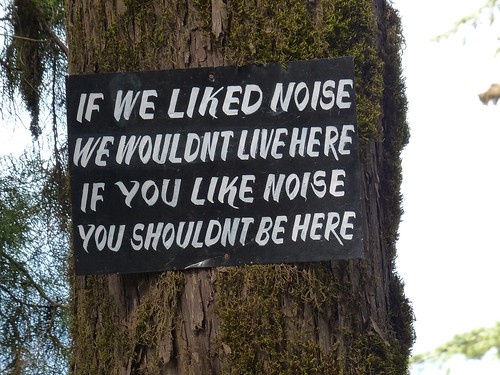

For the most part, we didn’t have to battle for space with other tourists. There were busloads of visitors, but the site was spread out enough to give everyone plenty of space. And people seemed to follow the rules outlined on this sign. The only shouting we heard was from a big group of school kids who discovered a classmate-sized langur monkey in their midst.

I have to admit I did tease my friends a bit and even snapped a few unauthorized photos … like this one. Rahman said many Buddhist monks from around the world make a pilgrimage to see the caves.

Cave 26 featured a larger-than-life reclining Buddha on his deathbed, blissfully drifting off to nirvana and into the arms of flying angels and musicians.

On the opposite wall, seven evil sisters fail in their attempt to seduce Buddha while their satanic father Mara watches from his perch on an elephant.

Very little of this cave went uncarved!

Cave 19 is considered the finest “chaitya hall,” or shrine, at Ajanta. The sign outside the cave says a feudatory prince was the generous donor for the cave in the 5th century AD.

Lonely Planet: “Notice the development from the stumpier stupas enshrined within the early chaityas to this more elongated version. Its umbrellas, supported by angels and a vase of divine nectar, reach right up to the vaulted roof.”

Eventually, we walked back to the beginning of the horseshoe to meet up with Rahman and visit Caves 1 and 2.

Hanging out with Buddha in Cave 1. Something that always strikes me at historical sites in Asia: We’re not only allowed to enter these caves and get close up and personal with the ancient art. We can actually plop down right ON the ancient art to mug for a photo. It’s both fantastic and tragic.

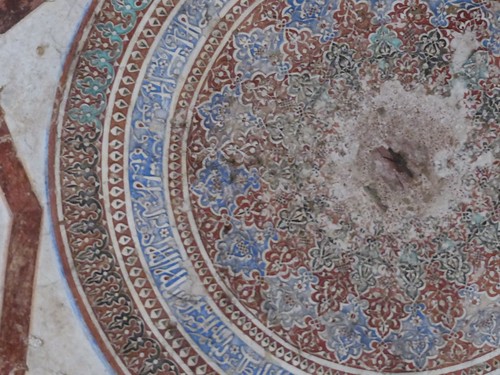

Check out the ceiling in Cave 2. This has survived since around year 500-ish. Insane.

Lonely Planet explains the painting techniques:

First, the rough-stone surfaces were primed with a 6- to 7-centimeter coating of paste made from clay, cow dung and animal hair, strengthened with vegetable fiber. Next, a finer layer of smooth white lime was applied. Before this was dry, the artists quickly sketched the outlines of their pictures using red cinnabar. The pigments, all derived from natural water-soluble substances (kaolin chalk for white, lamp soot for black, glauconite for green, ochre for yellow and imported lapis lazuli for blue), were thickened with glue and added only after the undercoat was completely dry. Finally, after they had been left to dry, the murals were painstakingly polished with a smooth stone to bring out their natural sheen. The artists’ only sources of light were oil-lamps and sunshine reflected into the caves by metal mirrors and pools of water (the external courtyards were flooded expressly for this purpose). Ironically, many of them were not even Buddhists but Hindus employed by the royal courts of the day. Nevertheless, their extraordinary mastery of line, perspective and shading, which endows Ajanta’s paintings with their characteristic other-worldly light, resulted in one of the great technical landmarks in Indian Buddhist art history.

When we arrived at Ajanta, touts harassed us to buy their wares. As we were leaving the site, the same touts descended.

One said to me, “I am Raj. Remember me from this morning? I have shop with postcards.”

“Hi, Raj,” I said. “I’m sorry, but I already bought some postcards.”

He looked so disappointed and whined, “But I TOLD you this morning, I have POSTCARDS.” Poor Raj.

Ellora Caves

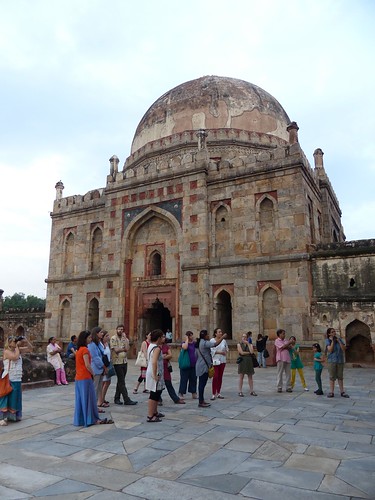

Day 2 of our visit to Aurangabad brought us to Ellora, another series of caves about 100 kilometers southwest of Ajanta. Here, 34 Buddhist, Hindu and Jain caves line a two-kilometer path along a volcanic ridge. This spot was located between two prosperous cities on a caravan route. Right about the time Ajanta was abandoned, a 500-year excavation of Buddhist caves kicked off at Ellora. That was followed by about 300 years of work on Hindu caves, and finally a group of caves from the 9th-11th centuries reveal the local rulers’ adoption of the Jain faith. We traipsed through in reverse chronological order, following the sunlight.

Cave 32 blew our minds. So unassuming from outside the gate …

… but chock full of decorative carving inside.

The two-story Jain temple was packed with sculpture, including Gomatesvara (one of the 24 religious leaders), who meditated in the forest so deeply that vines crept up his legs while animals and snakes crawled around his feet.

The upstairs shrine was dedicated to Mahavira, who taught a philosophy of non-violence and kindness to every living being. Check out the size of these pillars! The whole shrine was carved out of solid rock.

This website – The Ellora Caves – includes floor plans and heaps of photos that show what we saw in this cave (as well as all the other caves at Ellora).

From the Jain temple, we took a short ride to see the Hindu group of caves, starting with the most spectacular of all – Cave 16, the Kailash Temple.

Not really a cave at all, the temple was carved straight down 107 feet from the hillside. Krishna I initiated its excavation in the late 700s, but the whole project took 100 years to complete. Workers hauled away more than 200,000 tons of rock to reveal a replica of Mount Kailash, the Himalayan dwelling place of Shiva and Parvati. The temple’s snow-like lime plaster coating has mostly chipped away. Rahman pointed out that the temple took the shape of a massive chariot. Lonely Planet explains: “The transepts protruding from the side of the main hall are its wheels, the Nandi shrine its yoke, and the two life-sized, trunkless elephants in the front of the courtyard (disfigured by Muslim raiders) are the beasts of burden.”

The scale of this temple left us all breathless. From the ground looking up, and from the hillside looking down, we couldn’t fathom how such a perfectly proportioned and ornately decorated structure could emerge from the rock. I couldn’t believe I had never learned about the Kailash Temple in school. Its impressiveness ranks up there with Angkor Wat in Cambodia and the temples along the Nile River in Egypt, and yet I would never had known it existed if I hadn’t moved to India. It definitely inspired awe and gratitude on this Thanksgiving weekend.

Here are some details from Wikipedia:

Within the courtyard are three structures. As is traditional in Shiva temples, the first is a large image of the sacred bull Nandi in front of the central temple. The central temple – Nandi Mantapa or Mandapa – houses the Lingam. The Nandi Mandapa stands on 16 pillars and is 29.3 meters high. The base of the Nandi Mandapa has been carved to suggest that life-sized elephants are holding the structure aloft. A rock bridge connects the Nandi Mandapa to the Shiva temple behind it. The temple itself is a tall pyramidal structure reminiscent of a South Indian Dravidian temple. The shrine – complete with pillars, windows, inner and outer rooms, gathering halls, and an enormous lingam at its heart, is carved with niches, pilasters, windows as well as images of deities, mithunas (erotic male and female figures) and other figures. Most of the deities at the left of the entrance are Shaivaite (followers of Shiva) while on the right hand side the deities are Vaishnavaites (followers of Vishnu). There are two Dhvajastambhas (pillars with the flagstaff) in the courtyard. The grand sculpture of Ravana attempting to lift Mount Kailasa, the abode of Lord Shiva, with his full might is a landmark in Indian art.

For much, much more information, check out the Archaeological Survey of India’s website about the Brahmanical Group of Caves.

The story of the Ramayana.

Big bad-ass Shiva.

Inside the shrine.

The sacred lingam. Is it sacrilegious that it makes me feel icky?

After poking around the temple, we climbed up the hillside to see it from above. That’s Nancy, Lloyd, Kathryn and Katy. Yikes, it was a long way down.

Our guide, Rahman (top), sits with his friend, who was the tour guide for another bunch of AES teachers.

Well, nothing could compete with the Kailash Temple, but we did pop into one Buddhist cave before leaving Ellora. On the way, we saw these little cuties on a school trip eating lunch in the shade of a tree.

Cave 10 is known as Sutar Jhopadi, or “Carpenter’s Workshop,” because of the stone rafters carved in the ceiling. A caretaker opened the second-story balcony for us.

As we were leaving, a huge group of Indian tourists spotted Katy and accosted her for a photo, but Nancy grabbed her hand and pulled her away. I snapped this shot as I ran for safety.

Daulatabad

On the way back to the hotel, we stopped at Dalautabad. I remembered reading in William Dalrymple’s amazing book City of Djinns that the brutal Mughal ruler Tughluq relocated his empire’s capital from Delhi to Dalautabad in 1327, and he forced all of Delhi’s residents to WALK there – an 1,100-kilometer (683-mile) journey. And here we were, at the base of his hilltop fort! (Actually, occupation of the site changed hands many times since it was first used as a capital for Hindu tribes in the 9th century.)

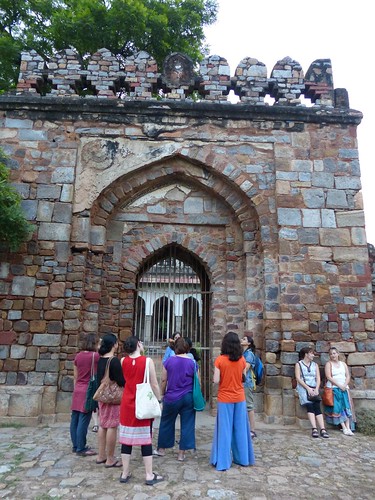

Rahman had us pause just inside the gate. He introduced us to the Jama Masjid, a mosque built by Delhi sultans in 1318, and the stone-lined “elephant tank,” which provided water to the fort and irrigated its gardens. We posed with these Muslim school girls on a class trip and shook their popsicle-sticky hands.

All day, I had been looking forward to climbing this hill, but Rahman said we didn’t have time.

Crestfallen, I asked how long it would take to walk to the top. “Two hours minimum,” he said. And how much time did we have to explore the site? “One hour,” he replied. Challenge accepted!

I bolted up the path, taking the steps two at a time. I paused to snap a few shots whenever I thought I was about to hyperventilate. The walkway twisted up and down stairs, through a series of fortifications, over a moat, into pitch-black tunnels reverberating with chirping bats and forking into dead ends before ultimately climbing to a 12-pillared pavilion. Breathless, I checked my time. 28 minutes! I took a quick shot of the pavilion and texted it to my friends with the message, “I made it! I’m about to throw up.”

I dashed into the structure and quickly admired the views.

As I prepared to head back down, I spotted one more look-out post perched right on the summit. Doh! Tempting, but I had to skip it.

Home Away From Home

Our group stayed at the Vivanta Hotel in Aurangabad. Despite a late afternoon chill in the air, I felt compelled to get in the pool both days. I didn’t mind the cold in my bones when I knew our room had a shower with hot water that lasted long enough to wash my hair AND body, unlike our shower at home. Such a treat!

Other notes of local interest …

For some reason, these ubiquitous langur monkeys don’t distress me the way Delhi’s macaque monkeys do. In fact, I kind of love them.

Aurangabad’s cattle featured painted horns. Rahman said everyone decorates their animals for a local festival each year in the fall. This guy has an Indian flag theme going on.

This was an after-lunch breath freshener at the Ajanta Caves restaurant. Fennel seed and sugar.