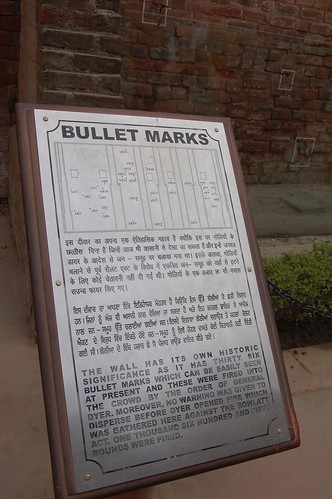

On April 13, 1919, thousands of people gathered in the Jallianwala Bagh, a garden down the street from the Golden Temple in Amritsar, for a religious celebration amidst a buzz of political restlessness. In the weeks preceding this day, tensions had escalated between British imperial authorities and activists for Indian independence. A series of protests and riots rocked Punjab, and rumors circulated that a revolt was planned for later that spring. To quell the uprisings, British governor of Punjab, Sir Michael O’Dwyer, declared martial law, which included a ban on public gatherings. When word of the crowd in Jallianwala Bagh reached Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer, he marched British and Gurkha troops into the garden and ordered them to open fire. His armored cars with mounted machine guns were too wide for the enclosure gate or he would have used those, too, he later admitted. Official figures put the death count at 379 with almost 1,200 injured, but other sources say close to 1,000 people were killed. More than 100 died by leaping into a well to escape gunfire.

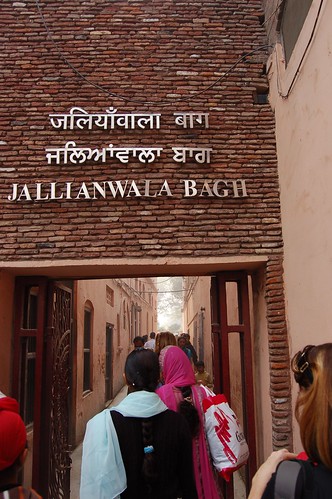

The garden now stands as a memorial to the massacre, so we stopped by to check it out. Entering the garden, we could envision people 92 years ago chatting under the trees and lounging by the stone wall, never suspecting the imminent ambush. Just as we were feeling appropriately somber, just as Jan was reading the story of the massacre from a guide book, we experienced a completely different kind of attack.

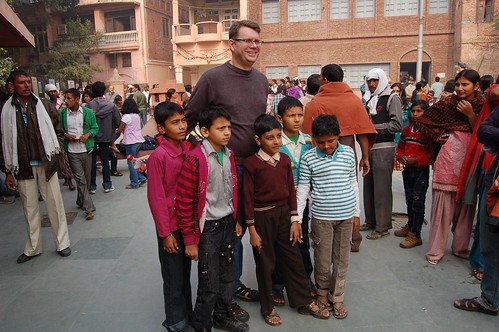

“On April 13, thousands of people gathered at Jallianwala Bagh in 1919. An hour after the meeting had started at 4:30,” Jan read, slowly raising her head from the book, “they were attacked by a wild mob of women in saris!” I looked around at the encroaching photo-seeking fans. We laughed but honestly couldn’t escape. Lucky for me, Jan created a diversion with her sing-song voice: “Well, hellllooooo. Oh, don’t you just look so beautiful! Well, I don’t know what you’re saying, but you’re absolutely adorable.” And so on. I slipped away and stared in shock at the group engulfing her. We had warned her not to make eye contact! We had tried to teach her the art of kind rejection, but there she was, trapped. I wish I could say that I parted the crowd and staged a daring rescue, but I am ashamed to admit I bolted for safety without a backward glance. Well, I looked back long enough to snap this picture.

I didn’t get far, however. Another group of smiling Indian tourists accosted me, rattling off Hindi louder and louder to help me understand. Finally, an English speaker asked where I was from, and I heard, “No British, American!” For once, being an American was an asset. It was far worse to be British in this emotional place. The group moved in closer. One lady embraced me, stroking my face and resting her head on my shoulder. She and her entire extended family insisted on cuddling and posing for phone photos, which took ages and left me a bit traumatized.

Finally, I was released to walk about the garden. But freedom was short-lived. Every time, I lifted my eyes from the ground, somebody was desperately bobbing around trying to catch my glance. Unlike the gentle snapshot requests at the Golden Temple, the memorial paparazzi were brutal. Although amusing, the attention really did keep us from fully experiencing the memorial and its displays. Next time, we’ll have to wear disguises.

Notice the girl taking a picture of me taking a picture of the memorial. ALL of my photos at the memorial have that common feature.

Can’t you hear their moms? “Go stand by the tall white man!”

These school kids were dying to bust out of that line and chat with us, but a nun with a stern face kept them in check.