Waving good-bye to the comfort of our swanky Petra hotel, Tony and I headed for Wadi Rum and Bedouin Directions camp. Our driver was named Jafar, so you know I couldn’t stop singing the Alladin theme song in my head for the whole 2-hour drive.

Our jeep tour organizer, Mehedi Saleh Al-Heuwaitat, had sent an email warning us of a scam at the Wadi Rum entrance gate: “Please don’t listen to the people who are waiting outside the Visitor Center building as they spend the whole day waiting to ‘catch’ tourists and they will lie with you quite happily and tell you they are me or work for me! They can be convincing but don’t believe them. I will not wait for you there, and a guide that works for me will not wait for you there. We will wait in the village. … Ask the guide meeting you to give you your name and if he can do this, you know you have the right people.”

Fortunately, Jafar bought our entrance tickets without incident, and we soon met up with Mehedi. He took us to his squat concrete home in the village, where we sat on the floor by the fire while his 3-year-old son played with cars in the gravel outside. Sipping tea, we chatted with another couple heading to the camp. After awhile, our guide Ahmed loaded us into a 4X4 jeep, and we rolled out of the village and into the desert.

We had almost cancelled this part of our trip because Tony’s persistent cough was taking its toll on us both. He felt pretty good during the day, so we stayed busy and active for most of our vacation up to this point, but every night was dreadful. Sitting up, he could catch a few minutes of sleep at a time, but if he tried to lie down, he erupted into horrible fits of coughing. He loaded up on drugs from a Petra pharmacy, but their effect was minimal. I was sleep deprived, and Tony was completely wrecked. Still, he insisted on going to the camp, and we both agreed it was one of our best days in Jordan.

South of the Shara mountains near the border with Saudi Arabia, Wadi Rum is one of several parallel valleys. Its deep red sand appears to flow like a river through canyons as it swirls around towering rock formations and sweeps up to steep dunes abutting the hills. The “jebels” – sandstone, granite and basalt mountains – rise up from the sandy valley as high as 800 meters (2,624 feet). Erosion over thousands of years has created the illusion of brick-red candle wax dripping down the hillsides.

Ahmed drove his jeep across the red sand as though signs pointed to our destination, but the only signs I could see were were rocks, scrubby bushes, sand dunes and mountains. He didn’t speak much English, but he was friendly and tried really hard to answer our questions. We stopped at several spots to scramble on the boulders, hike up to a viewpoint or play on the sand dunes.

Throughout the day, Ahmed would point to something and reference Lawrence of Arabia. At first, we thought the movie was filmed here. Then we thought maybe the real Lawrence of Arabia lived here. It wasn’t until we got to Amman with internet access that I found answers. Well, sort of. Even the most credible websites conflict each other regarding T.E. Lawrence, the British army officer who lived and fought among the Hashemite rebels against the Ottoman Empire in World War I. Bottom line: T.E. Lawrence did spend some time in this region around 1917, and the epic movie starring Peter O’Toole was filmed here in the 1960s. In his book The Seven Pillars of Wisdom, Lawrence described Wadi Rum as “vast and echoing and God-like,” using the Latin phrase “numen inest” or “There is divinity here.”

The Smithsonion Magazine’s article, “The True Story of Lawrence of Arabia” from July 2014 provides a fascinating and in-depth look at Lawrence’s life and relationship with the Arab world.

Our jeep tour of Wadi Rum included these stops.

Abu Aina – Misidentified as Lawrence Spring, the water here actually trickled down to the desert from the real Lawrence Spring a bit higher up the mountain. We climbed up the boulders to find a little pond of water and see the view. A couple fig trees provided shade at the top.

Small Sand Dunes – We climbed, posed, marveled at the landscape, and then Tony ran down the dune.

Khazali Canyon – This short canyon required shuffling along a narrow rock path and then using the natural handholds in the rock to climb past a pool of water. At the end, a slippery vertical wall seemed like an exciting challenge, so I started my ascent. Thanks to erosion, the wall was pockmarked with cracks and steps. However, about halfway up I suddenly panicked that I was free climbing with no ropes and no belayer. I wasn’t completely confident I could get back down without rappelling. My legs started trembling, and I slowly backtracked to the ground. Walking out of the canyon, we encountered that first puddle again, and I knew I could get across with no problem. However, a big group of tourists approached with a bossy guide, making me nervous. My foot slipped and splashed into the water up to my shin. Embarrassing.

Red Sand Dunes – More climbing, posing and enjoying the view. See a pattern here? After owning my camera for two years, I finally figured out how to take panorama photos without overexposure. Yay!

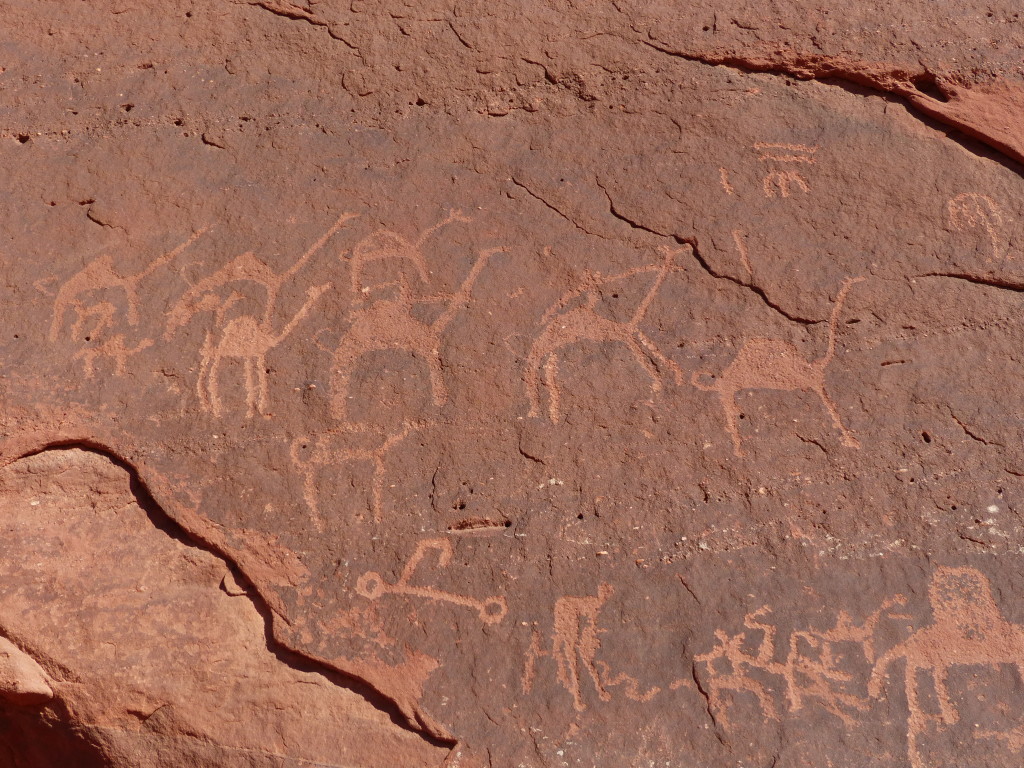

Anfishieh Inscriptions – Despite way too much time researching this on the internet, I couldn’t find anything authenticating these inscriptions. The rock drawings are generally attributed to the Thamudic and Nabataean tribes, so they could date back to the 8th century BC. All Ahmed could tell us was that they were “very old.” There was definitely some modern graffiti alongside the very old drawings, unfortunately.

House of Lawrence – A small structure possibly built by the Nabataeans possibly may have been used by T.E. Lawrence to store weapons during the Great Arab Revolution. Possibly. Regardless, a short climb above the structure offered up yet another stunning view. Ahmed found a nook in the rock nearby, built a fire and whipped up a delicious lunch for us while we explored.

Tony had an extra pair of socks in his backpack, so I was able to change out of my wet one.

Mushroom Rock and Roman Dam – After a short stop at this bulbous rock, Ahmed took us to a dam that he said was built by the Romans. He said the dam creates a basin for rainwater, which can be piped out for watering camels, goats and sheep.

Barragh Canyon – Ahmed dropped us off at one end and picked us up at the other end. I hadn’t realized until later that this was a big attraction for rock climbers. Rats, that would’ve been fun.

No doubt about it, nature is cool. I’m always amazed to see where living things can thrive, and Tony and I both couldn’t stop commenting on how the earth morphs. Every step brought us more evidence that this region had been under water at one time, rocked by earthquakes and slowly sculpted by sand, water and wind.

Burdah Arch and Um Frouth Arch – We viewed the Burdah Arch from a distance. Ahmed said it takes about three hours to hike to the top. Instead, we visited the much more accessible Um Frouth Arch. Only about 15 meters high, it was narrow enough to inspire some serious fear. I gripped Ahmed’s arm pretty hard as we stepped closer to the edge. He then laughed and showed me how he could get down from the arch in 3 seconds … in sandals. And he did. Yikes.

Finally, we stopped at Chicken Rock, a big ball on two legs, which I failed to photograph, and climbed up the adjacent rock with a few other tourists to watch the sunset.

I like this shot of Ahmed, Tony and my shadow.

After the sunset, Ahmed drove us to our campsite. We approached Bedouin Directions through a crack in the rock and found the tents protected by high cliffs on all sides. Our tent included four beds, but Tony and I had the place to ourselves. The two toilets were a short walk away.

After warming up by the fire in the communal tent, we ate a delicious dinner. One of the camp guides called us outside to watch him unearth the zarb from the sand. The website Jordanian Foods explains this style of cooking:

As ancient and traditional cooking practices go, the zarb is perhaps the most dramatic. It consists of lamb or chicken, sometimes herbs and vegetables, which have been buried in an oven with hot coals beneath the desert sands. When it’s time for the meat to resurface, the sand is brushed away, the lid comes off, and the glorious slow-roasted fragrances billow into the air.

For centuries the bedouin have been cooking like this throughout the Arabian peninsula. When tribesmen roamed across the desert in search of water and pasture for their animals, they kept their cooking equipment to the bare minimum. An earth oven could be dug quickly, and hot embers and stones from the campfire could be placed inside. The meat would be wrapped in palm leaves, and a mound of sand would seal in the heat.

Despite wearing long underwear, two long-sleeved shirts, flannel pajamas and my wool hat, and despite burrowing into a silk sack and under the thick blankets, I was freezing. There was no way I was getting up to pee during the night. The combination of the cold and Tony’s coughing meant another sleepless night. No matter. It was otherwise a perfect day and wonderful experience.