I toured Delhi’s Toilet Museum today, thinking it would be good for a laugh. And it was. (Potty jokes never get old, right?) However, more importantly, the museum’s light-hearted approach to toilet history effectively lifts the conversational taboo and lures unsuspecting visitors into learning about India’s sanitation crisis and one organization’s efforts to address it.

Sharon Lowen, the American Embassy School’s Community Programs Coordinator, led the tour to the Sulabh International Social Service Organization complex.

In the Toilet Museum, a guide summarized the displays, pointing out images of 4000-year-old stone toilets and drainage systems from the ancient civilization in Harappa, a model of a mobile toilet (India’s version of the porta-potty), sketches linking Europe’s bubonic plague epidemic with poor sanitation practices, a humor nook plastered with toilet-related jokes and cartoons, and a vast collection of actual toilets. These included a replica of French Emperor Louis XIV’s throne-like chamberpot, ornately painted Victorian-era toilets, a tent-enclosed camping toilet, an electric toilet that incinerates waste on-site, and a small table with a surface that lifts up to reveal a pot. (“So they could eat on it and shit in it,” the guide said. Side note: “Shit” doesn’t seem to be as offensive in Indian English as it is in American English, so it’s often used in casual conversation in its literal form.)

According to Sulabh’s website, Founder Bindeshwar Pathak was inspired by Gandhi’s call to abolish “scavenging,” the cleaning out of bucket toilets, pit latrines and other open sewers by hand. Scavengers – people from the “untouchables” caste – often pile the waste in baskets to carry on their heads as they walk long distances for burning or disposal. Outlawed in 1993, the practice continues with some estimates approaching 800,000 scavengers in India. In addition to the health hazards and degradation faced by scavengers, the lack of operational toilets also wreaks havoc on the environment, keeps girls away from schools and forces women to seek out privacy in dangerously dark outdoor areas before sunrise.

Dr. Pathak decided to “use the toilet as a tool for social change,” the Sulabh website says. He developed an eco-friendly, twin-pit toilet that naturally composts the waste, providing a culturally acceptable and affordable option for individual households. The toilet uses only a liter of water to flush the waste into one of the covered pits. When the pit fills, it is closed off and allowed to compost for several years while the waste is channeled into the second pit. When the second pit fills, it is closed for composting, and the first pit is re-opened. The dry composted waste from the first pit is removed for use as fertilizer, and the toilet water is channeled once again into that pit.

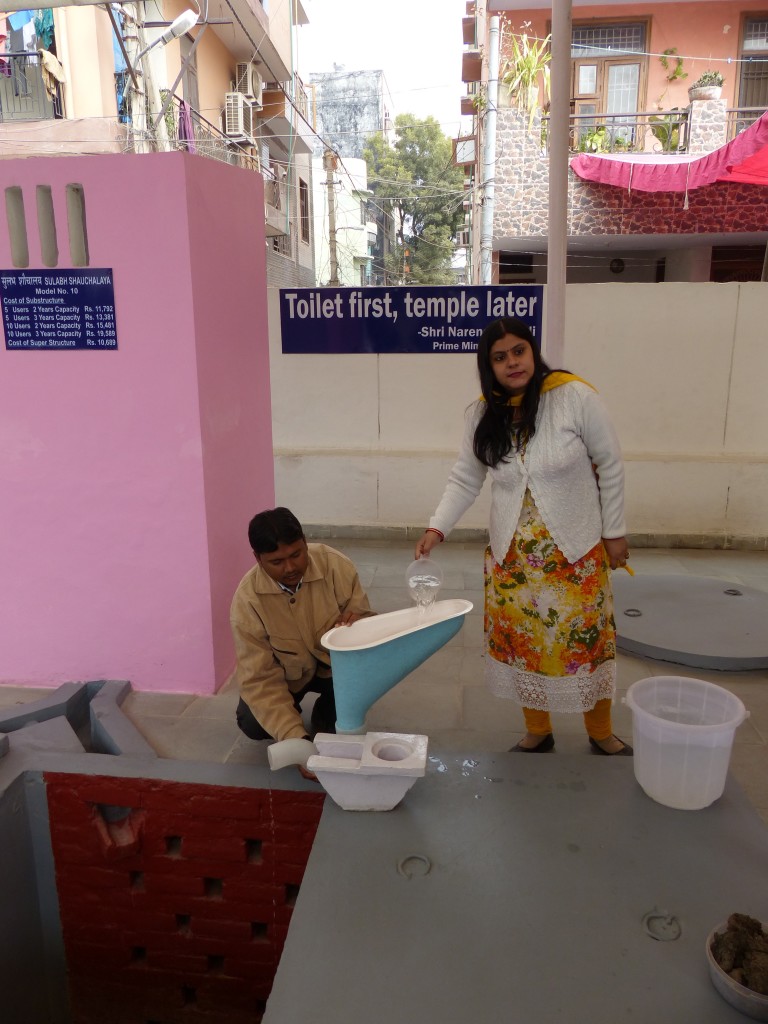

At the Sulabh complex, we checked out several varieties of the toilet. Sulabh Vice President Nigar Imam explained that the toilet technology works in any region. Depending on geography, the pits may be lined with cement, stone or wood coated with tar. The toilet may be fully enclosed with brick walls and a roof, circular with no door or roof, made of bamboo mats or jute, or otherwise constructed to meet the desires and needs of the family. “Some people want the moon, sun and breeze,” said Ms. Imam.

Ms. Imam uses props to demonstrate how little water is required to flush the toilet.

This model was specifically designed for homes with limited outdoor space for constructing a toilet.

A brochure offered at the complex includes a picture of a spacious WC with a tile floor, windows and a door. “Sulabh two-pit pour flush toilets can be constructed by even rich people where there is no sewerage,” it says. “The pits can be cleaned after 40 years.”

During our visit, Dr. Pathak made an appearance and posed with our group. He expressed optimism that Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi “has ignited the minds of Indians about sanitation and hygiene.”

Modi launched his Clean India Mission campaign in 2014 with the goal of ending open defecation and generally improving sanitation across the country by March 2019 in honor of the 150th anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi’s birth. “Toilet first, temple later,” he said.

About 120 million toilets must be constructed to meet that goal, says Dr. Pathak, calling on wealthy individuals, companies and organizations to contribute. An individual toilet system costs about $500.

Sulabh is doing its part. Some achievements:

• 1.3 million Sulabh household toilets constructed

• 54 million government toilets constructed based on the Sulabh design

• more than 8,500 Sulabh community toilet blocks constructed

• Scavenging eliminated in 640 towns

After introducing us to the toilet systems, Ms. Imam explained that Sulabh also developed technologies for converting waste from public toilets into biogas and for recycling the run-off into water for cleaning or irrigation.

At the entrance to the Sulabh complex, the public can take advantage of squeaky clean toilets, cheap drinking water and a small primary care clinic, where doctors offer free consultations and medication to those in need.

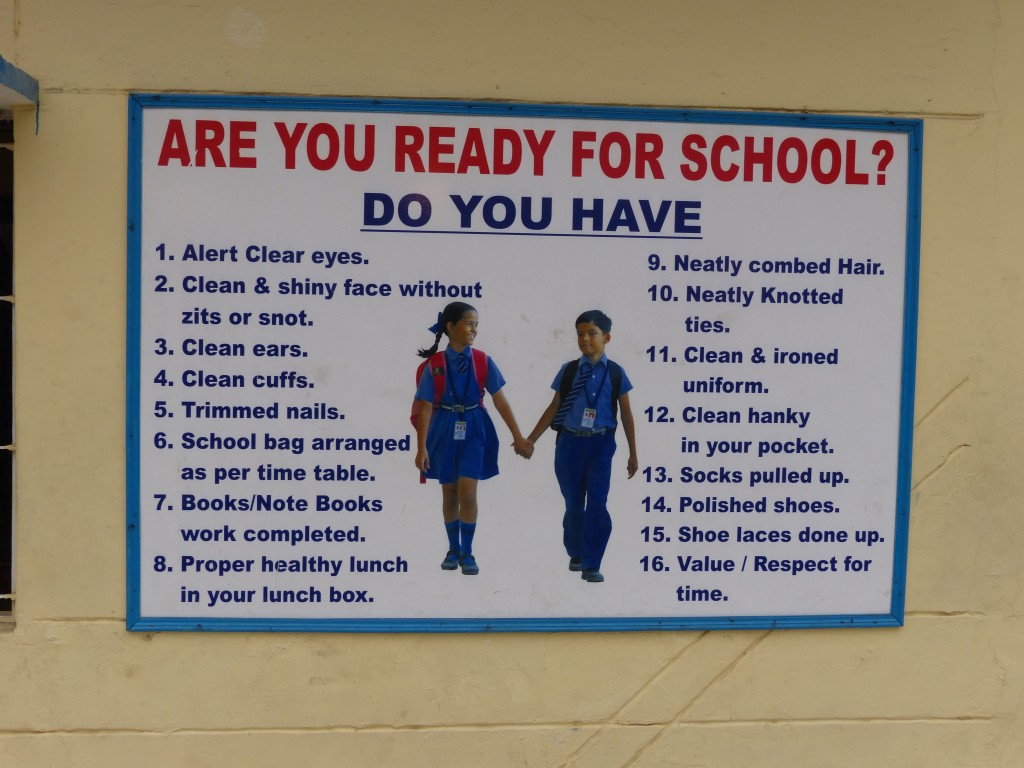

Sulabh also operates an English-medium school with free tuition for underprivileged children, who comprise about 60 percent of the student population. Graduates and adults benefit from Sulabh’s occupational training classes. When we arrived at the complex, the school children were gathered for a ceremony to celebrate Vasant Panchami, a festival in honor of the Hindu goddess of wisdom and knowledge, Saraswati.

Living in Delhi, I frequently find myself discouraged and worried about India’s future. After visiting Sulabh, meeting Dr. Pathak, and reading up on the work of this organization, I feel a new glimmer of optimism.

For an excellent profile of Dr. Pathak, check out “Soldier of Sanitation.”