After regrouping outside the Machu Picchu historic site, we were all ready to take a bus back down the mountain, when Ian lost his dad.

The line for the buses snaked out of sight, so Ian and Stella took the girls to the café to get a snack, but Peter was nowhere to be found. I searched for awhile in vain while Tony held my place in line. Eventually, he turned up, after enjoying a cocktail in the swanky Hiram Bingham Hotel.

We all retrieved our luggage from our hilltop hotel and met at the train station for the short journey to Ollantaytambo.

I love arriving at a destination in the dark and then waking up in the morning to see where you are. That’s what happened here.

In the mid-15th century, Ollantaytambo was conquered by Inca Emperor Pachacuti, who rebuilt the town to serve as his personal estate. Laid out in a grid with narrow crisscrossing cobblestone roads, the village remains much as it was at that time.

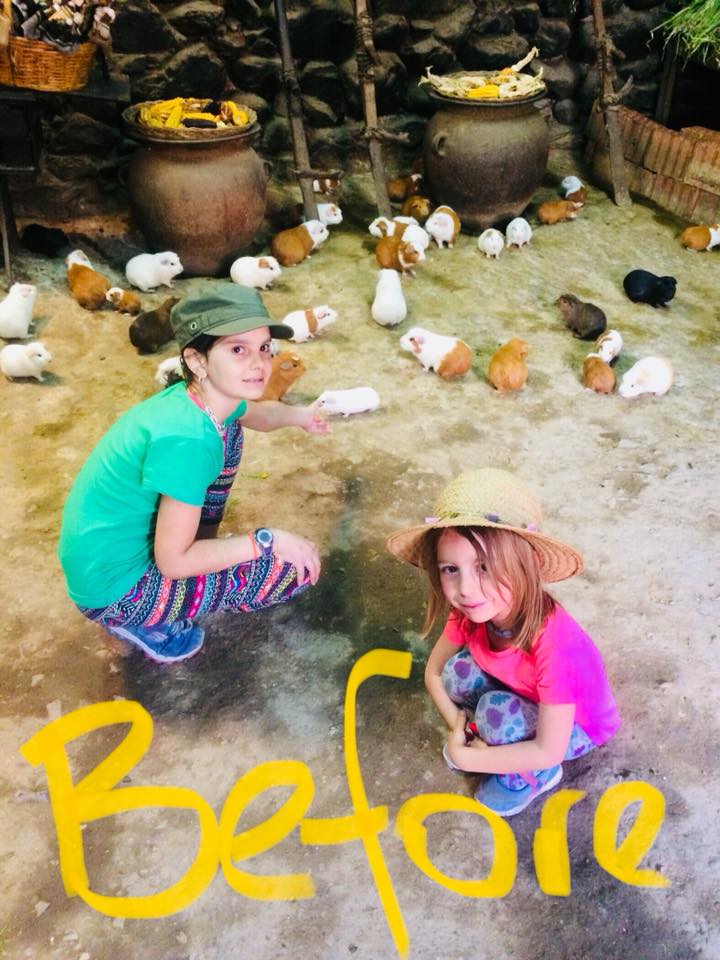

People still live in the original one-room homes in small walled compounds with a central courtyard. We popped in to one of the homes, where tour guides had brought visitors for a glimpse of “real” life. A couple beds were pushed up against the wall, and scores of guinea pigs ran loose, dashing under the beds to avoid the tourists’ clunky hiking boots. We assumed this painting depicted the homeowners.

Stella’s girls posed with the home’s inhabitants. After sampling quite a few guinea pigs during our trip, Stella morbidly portrayed the likely fate of those little tourist attractions.

Hanging out in the village, we watched people going about their regular business dressed in colorful Andean clothing.

This lady had a lamb in her backpack.

Some locals know a good thing when they see it, so they approach tourists for a few soles in exchange for a photo. These little guys sang for us while we ate dinner.

Of course, the real draw of Ollantaytambo is its ruins. Tony and I toured the site with a guide named Julissa. She explained that Emperor Pachacuti started construction of a massive temple on the steep hill called Cerro Bandolista. The stones came from the Chachiqata quarry across the 1,000-foot deep valley.

This “Wall of the Six Monoliths” was part of the unfinished sun temple. Each stone weighs up to 100 tons. How did they move these from the quarry? How did they cut the stones so perfectly? Nobody knows.

In addition to the temple, the site features agricultural terraces climbing up the mountainsides. Farmers grew potatoes, quinoa, corn, flowers, and medicinal plants.

In the Smithsonian article, “Farming Like the Incas,” archaeologist Ann Kendall describes the engineering genius of terracing:

The terraces leveled the planting area, but they also had several unexpected advantages, Kendall discovered. The stone retaining walls heat up during the day and slowly release that heat to the soil as temperatures plunge at night, keeping sensitive plant roots warm during the sometimes frosty nights and expanding the growing season. And the terraces are extremely efficient at conserving scarce water from rain or irrigation canals, says Kendall. “We’ve excavated terraces, for example, six months after they’ve been irrigated, and they’re still damp inside. So if you have drought, they’re the best possible mechanism.” If the soil weren’t mixed with gravel, points out Kendall, “when it rained the water would log inside, and the soil would expand and it would push out the wall.” Kendall says that the Incan terraces are even today probably the most sophisticated in the world, as they build on knowledge developed over about 11,000 years of farming in the region.

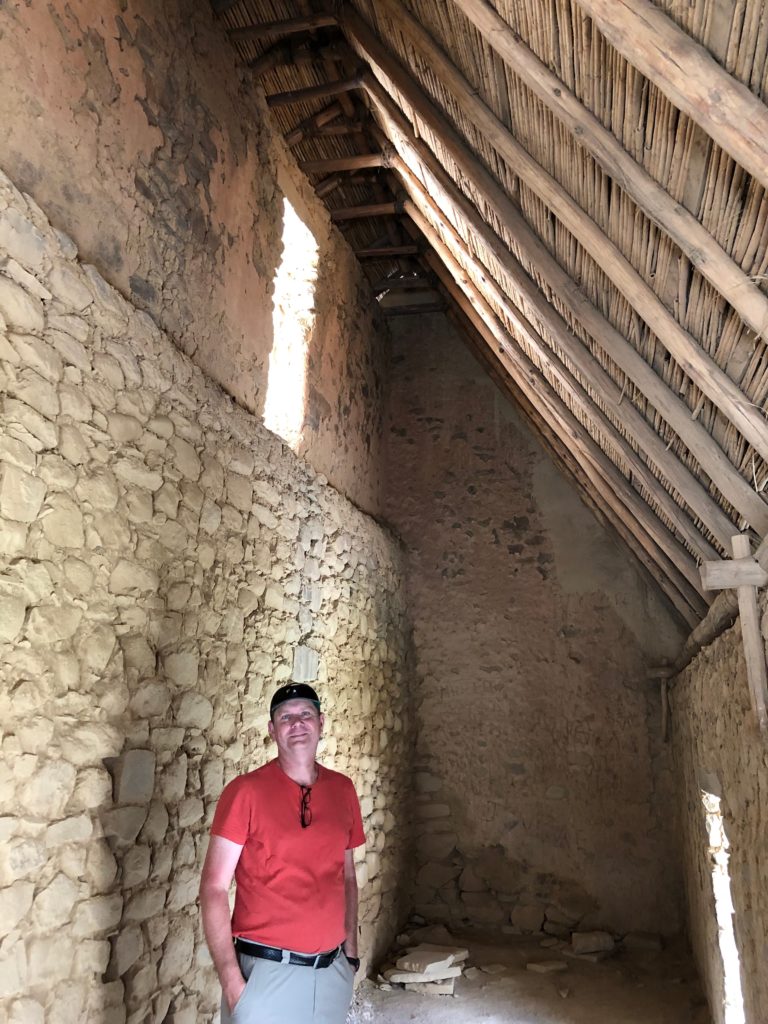

Our guide, Julissa, also showed us Incan storehouses designed for optimal air circulation. Grain was dumped in the top and collected at the bottom.

Our tour continued through a funerary sector and down to a series of canals and fountains, evidence of the ancient irrigation system.

Emperor Pachacuti mysteriously abandoned construction of his temple, but the hill served another important role after the arrival of Spanish conquistadors. In the Battle of Ollantaytambo, the head of the Inca resistance, Manco Inca, led about 30,000 men to fend off an attack by an expedition of Spaniards under the command of Hernando Pizarro. Standing at the top of the hill, looking over the valley, I wondered how Manco Inca felt about the inequity of his plight. His band of conscripted farmers, armed with machetes and other rudimentary weapons, faced soldiers who had the advantages of armor, horses, and guns.

If, like me, you want to spend hours learning more about this stuff, here’s one interesting summary about the Spanish conquest of Peru on the Heritage History website.

I still felt a little stupid for not getting a guide at Machu Picchu, but touring the Ollantaytambo ruins with Julissa made up for it.

All that walking and talking in the hot sun meant only one thing. Time for a beer break.