At the Livit Immersion Center, our class wrapped up at 1 p.m. each day. After lunch on Mondays, Tuesdays, and Wednesdays, each student was matched with a personal guide for some intensive Spanish practice while checking out Puebla’s attractions. As a UNESCO World Heritage Site, this city has no shortage of historical sites. (Here’s a long but fascinating story about Puebla from the Smithsonian website.)

It almost didn’t matter where I went with my guide. It was pretty hard to maintain a conversation in Spanish while paying attention to where I was walking or what I was seeing. I usually focused on the guide’s face and tried not to trip over uneven pavement. Good thing I took some photos!

My first week, I hung out with Noemi, an adorable young woman who spoke slowly and clearly so that I understood almost everything she said.

Week 1, Day 1: Our first day together, she showed me the historical town center, known as “el Zócalo.” Flanked by the Cathedral of Puebla on one side and a colonnade of colorful buildings – including Palacio Municipal, Puebla’s town hall – on the other three sides, el Zócalo was established as a marketplace in 1531, but is now a tree-filled park.

Noemi and I breezed through the Amparo Museum, where I could have easily spent the whole day. I didn’t take many photos inside, but the space was fantastic. Housed in two colonial-era buildings, the museum juxtaposes 4,000 years of history with modern multi-media art exhibits.

Here I am posing on the rooftop terrace.

Week 1, Day 2: Noemi took me to one of my favorite destinations in Puebla, the Museum of the Mexican Revolution, also known as Casa Hermanos Serdán. As someone who learned very little (nothing?) about Mexico in school, I was blown away by the fascinating story surrounding the beginning of Mexico’s revolution, which ended a dictatorship and established a constitutional republic.

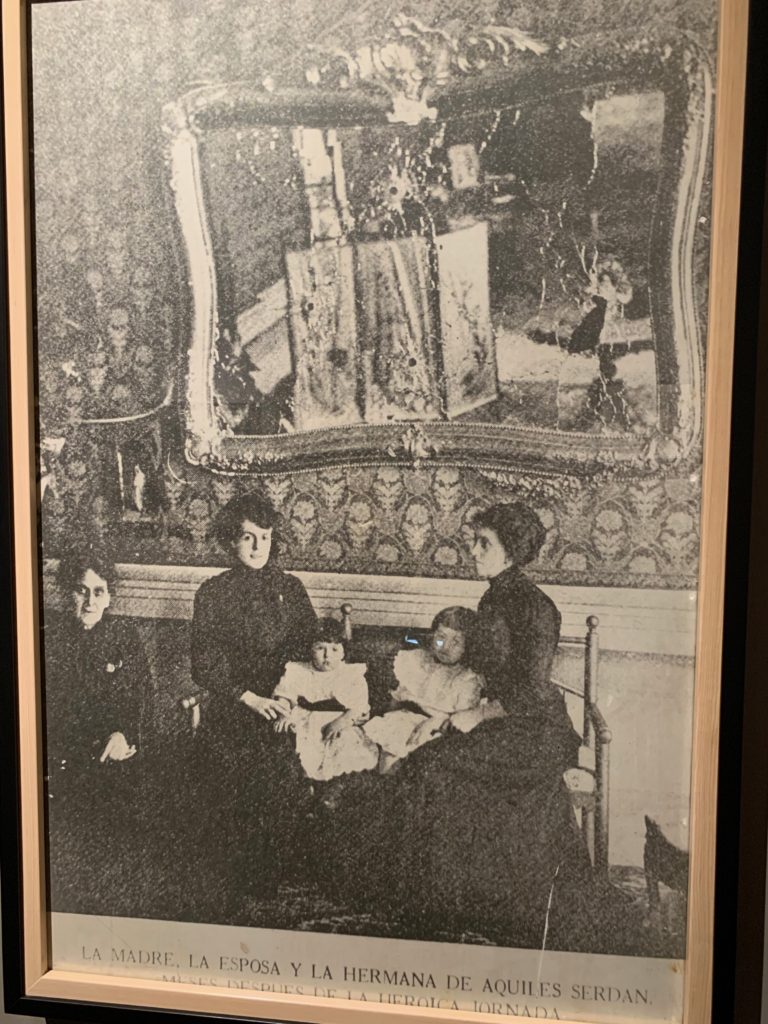

The museum is housed in the former home of the Serdán family, which included brothers Maximo and Aquiles, as well as their sister Carmen. They had been pivotal in planning an uprising led by Francisco I. Madero against the government of President Porfirio Díaz in 1910, but the plot was discovered. On Nov. 18 of that year, the chief of police approached the house with a warrant for Aguiles’ arrest, but he was shot and killed. Soldiers and police surrounded the house, and a 3-hour shootout ensued. The Serdáns and their supporters were vastly outnumbered. Maximo was killed after hiding his brother under the floorboards. When Aquiles tried to escape the next day, a soldier spotted him and killed him. Carmen and her mother were captured and imprisoned.

The revolution officially kicked off two days after the shootout at the Serdán home. President Porfirio Díaz stepped down in May 1911. The Serdán family is revered in Puebla for their bravery and contributions to the revolution.

Artifacts in the museum recreate the era with interpretive signs in Spanish and English. I was fascinated by the arrangement that matched the photo, including the bullet-riddled mirror.

Noemi and I sat for a while and watched a movie that recreated the story of the shootout.

The pockmarked facade of the home reminds passers-by of the shootout that marked the beginning of the Mexican Revolution.

Week 1, Day 3: Noemi and I took an uber to check out “los fuertes,” where I learned that Cinco de Mayo is not just an opportunity to wear a sombrero and pound tequila shots.

According to the Cinco de Mayo article on the history.com website, Cinco de Mayo celebrates the victory of the Mexican army over France at the Battle of Puebla during the Franco-Mexican War on May 5, 1862.

When Mexico defaulted on loans from Europe, Spain and Britain struck a deal with the Mexican government, but France launched an attack in 1861. President Benito Juárez “rounded up a ragtag force of 2,000 loyal men—many of them either indigenous Mexicans or of mixed ancestry—and sent them to Puebla,” the article says. They faced an attack of 6,000 French troops, who retreated after a full day of fighting and a loss of about 500 men.

The battle took place on hillsides in Puebla topped by the Fort of Loreto and the Fort of Guadalupe, both originally built as chapels and converted to museums.

Noemi and I strolled around the hill, enjoying the views and chatting about her life. We didn’t go inside the forts or any of the many museums in the huge area known as Centro Cívico Cultural 5 de Mayo. That was fine with me. I needed some tranquility, and this park delivered.

We walked down the hill and back to the historic town center, passing first through Barrio de Xanenetla, a neighborhood that had fallen on hard times until the community pulled together through a street art initiative.

On our way back to my ‘hood, Noemi took me down Cinco de Mayo St., which crackled with life. The street was full of people shopping, performing, selling street food, resting on benches, eating ice cream, hawking balloons, chatting on phones, waiting for buses, pushing strollers, and doing all the things regular people do. “This is real,” Noemi said to me (only in Spanish). “Where you’re staying is historical, more tranquilo, but this is real life.” At that point, she spotted a toy store and bought a mini hula hoop for her daughter.

Week 2, Day 1: New week, new guide. This time, I was assigned to Pedro, a nice young guy who was passionate about the history of Puebla. We tagged along with another student, Zoe, and her guide, Angelica, to learn more about Puebla’s famous talavera industry.

Indigenous people in Mexico have been producing pottery for thousands of years, but new techniques and motifs arrived from Europe with the Spanish conquest. According to the website of the workshop we visited, Talavera de la Luz:

During Colonial times, Spaniards started bringing ceramics from Europe, as well as establishing Spanish potter workshops. Puebla was the main pottery production center not only of the New Spain, but of the New World. In 1550, 20 years after the city was founded, it already had several workshops of glazed pottery and tiles which would later be known as Talavera de Puebla and that, from that time, became the best known type of ceramics in the country and one of the oldest crafts in Mexico. Its name comes from the place of origin of the first artisans which produced it and from the fact that the techniques used copied those used in the town of Talavera de la Reyna, in Spain.

Before visiting the Talavera workshop, Angelica suggested we stop at a “taller de barro,” or workshop of clay. This was the highlight of my day! The workshop was located in a narrow alley full of smoke from the fire that heated the kiln. We watched a guy making chalices that are used during Day of the Dead (for candles or incense, I think). The maestro of the workshop showed us around and gave a ton of information. I tried really hard to pay attention and understand, I swear. But after awhile, I just got distracted. There was so much to see. I do recall him saying that they produce different items, depending on the season and the upcoming holidays. Oh, and he said a piece takes 15 days from start to finish.

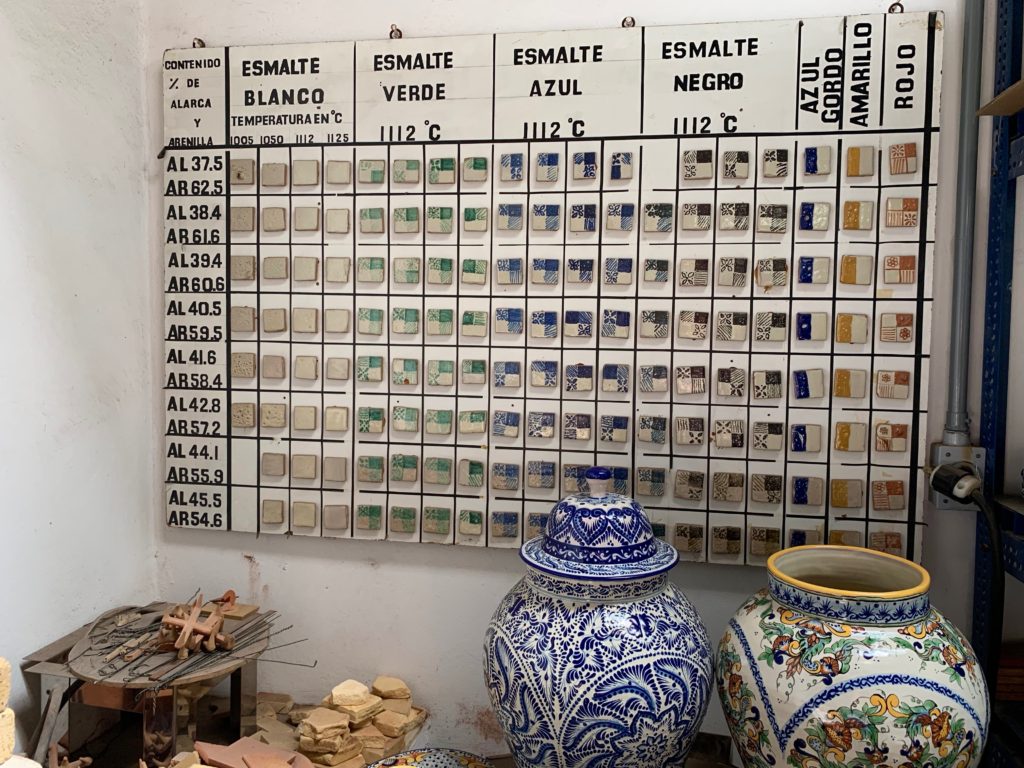

Next, we visited the much swankier Talavera de la Luz, which produces the real deal – only nine workshops are certified by the regulatory body Consejo Regulador de la Talavera, and it’s one of them.

Week 2, Day 2: Today Pedro and I just wandered aimlessly around town. There was a huge festival celebrating the Day of Our Lady of Mount Carmel. Since my casa was very near the church honoring her, our neighborhood was bonkers. We strolled through the festival for a bit, checking out all the food and wares. It was hard to take photos because of the crowds and the low awnings over the booths.

We were leaving the festival when I saw this little show of Lucha Libre! So hilarious!

I wanted to buy some traditional candy as gifts for people back in Chile, so Pedro took me to the Calle de los Dulces (Street of Sweets). I loaded up on camotes (cigar shaped treats made from sweet potatoes), Tortitas de Santa Clara (little shortbread pies with a pumpkin seed filling), jamoncillo (a milky fudge), and more. He also took me to a great little chocolate shop, La Casa de Robertina, where I bought a few more gifts (for myself) and some fancy coffee for my hosts.

On the way back to my house, I was feeling exhausted. I really just wanted to plop on the sofa with a beer. I stopped by a convenience store and bought a beer and some cookies, but then I got a bit embarrassed about it. I didn’t want my hosts to find an empty beer can in my room. So I drank it in secret and then stashed the can in my bag so I could throw it away outside the house. I felt like an underage college student. What has happened to me?

Week 2/Day 3: For my last day with a guide, I really just wanted to chill. I was so mentally and physically exhausted. Jacinda had recommended a nice little museum with an interesting art exhibit. I told Pedro I wanted to see that, and afterwards I thought he and I could hang out at a coffee shop for the rest of the afternoon. Instead, we walked for about 800 miles because Pedro’s maps app kept giving him incorrect directions. I wanted to scream. Finally, we asked some people for directions and walked another 800 miles to find the museum at La Universidad de las Américas Puebla. Two artists were spotlighted: Paloma Torres and Miguel Covarrubias.

Torres’ art included felt work tapestries, stone sculptures, large columns, and other works inspired both by the natural world and big cities.

Covarrubias was a painter, caricaturist, illustrator, ethnographer, and historian. His work was featured in Vanity Fair and the New Yorker magazines, and his style influenced artists around the world. I went down the internet rabbit hole reading about him. What an interesting and accomplished man. Here’s a fun read from the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery website. Pedro poses with one of Covarrubias’ maps, which was made for Goodyear as a promotional give-away.

To be honest, I could go the rest of my life without visiting another church, but Pedro said I couldn’t leave Puebla without seeing La Capilla del Rosario. The church was closed when we got there, so we killed a little time by visiting the museum next door, Museo Jose Luis Bello & Zetina. It was pretty interesting. According to a sign on the building:

The historic house museum has retained its original furniture from the 19th century, mainly from Europe. Its heritage is enriched by a series of silver, bronze, glass, marble and porcelain articles. The house holds the art collection that was part of the convent of the Order of Santo Domingo de Guzman. With the “Reform Laws,” the friars were expelled from their property in 1861 and a large part of the convent was destroyed. The rest was sold to private parties. Mr. Jose Luis Bello y Gonzalez, grandfather of our collector, bought the part of the convent that was the former pilgrim portal, adapting the lower floor for offices and constructing a private dwelling on the upper floor where Mr. Rodolfo Bello y Acedo lived; he bequeathed it to his son, Mr. Jose Luis Bello y Zetina, upon whose death it was given to a foundation to establish the “House Museum.”

When we came out, the church was open, so we popped in. Holy crap, I now see why this place is famous. The chapel is housed in the Church of Santo Domingo, which was fancy enough.

But then we turned left into the chapel, La Capilla del Rosario, and my jaw dropped. The 17th-century chapel is literally dripping with gold, 23-carat gold leaf to be precise. According to this Atlas Obscura article, “Its purpose was to honor the Virgin Mary as well as to teach the locals the practice of the rosary, of which the Dominicans (the order in charge of the temple), were ardent promoters.” Pedro and I chatted a bit about how hard it is to justify that much money going toward decorations when the church’s mission is to help the poor. But such is life.

Hanging out with the guias was both the most challenging and the most useful part of my Spanish immersion experience. I both dreaded and looked forward to it each day. I knew it was important for my language development, but holy moly, it was mind-numbing. Thanks to Noemi and Pedro for their patience!