As a high-schooler in Germany, I felt pretty special to dance the night away (in my red lace gloves) at prom in the Heidelberg Castle and walk down the aisle in my purple cap and gown for graduation at the historic Worms Cathedral. Hard to beat that, I thought.

Well, not really.

Tony and I just got home from a staff retreat at a 15th-century fortress in Rajasthan, India. Quoting from “30 Rock,” Tony called it “the retreat to move forward,” but there were no cheesy team-building games or activities with awkward compulsory sharing. Just a lot of chillin’ and “Princess Bride” jokes (Have fun storming the castle!).

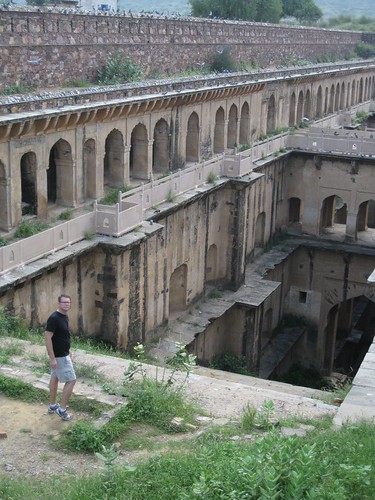

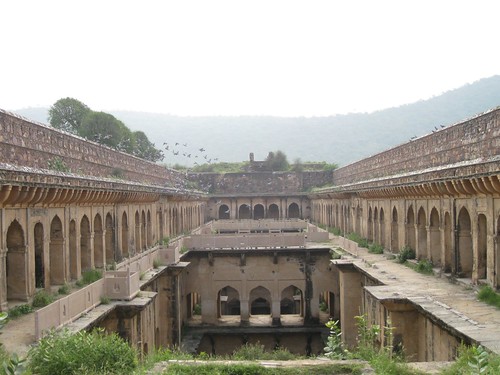

More than 50 teachers (plus a few non-teacher spouses and kids) traveled to the Neemrana Fort-Palace, which sits on a plateau at 1,640 feet, about three hours’ drive from New Delhi. The 2-billion-year-old Aravalli Mountains serve as a backdrop.

Built as a fortified palace starting in 1464 AD, Neemrana served as home to descendants of northern India’s last independent Hindu king, Prithviraj Chauhan III. Chauhan was defeated in battle and executed by Mohammad Ghori in 1192 AD, ushering in an era of Muslim rule. When India attained independence in 1947, royal privileges were ultimately abolished, leaving Maharaja Rajendra Singh strapped for cash and unable to maintain the crumbling fort. Thirty years later, entrepreneurs with a vision purchased the ransacked, dilapidated ruins and renovated the fort into an upscale heritage hotel.

I loved climbing up and down the zig-zagging wedding cake stairs of this ancient funhouse to discover interesting nooks at every level. However, just getting from our room to the restaurant involved a serious quad workout and a copious amount of sweat, so you can imagine our disappointment when we saw the algae coating on the surface of the pool. Some teachers and their kids crossed their fingers and dove in (after consulting with the hotel and checking Ph levels), but I’ve already done a round of antibiotics in India and didn’t feel the need to contract anything new at this juncture.

The green pool was disheartening for several reasons. Tony had fantasized about escaping Delhi’s oppressive heat with a refreshing dip, and I was looking forward to socializing poolside with our new colleagues. The crowd did gather around the steamy pool area, but I shunned the bonding opportunity in favor of the cool spa.

Our room – the Gujarat Mahal – was whitewashed and decorated with interesting art and period furniture. Small arched windows inside bigger arched niches overlooked the grassy valley, and the marble bathroom was reminiscent of a Turkish hamam.

Shots from around the fort. (The one of Tony and Mr. Singh is for you, Mom!)