From Ollantaytambo, we drove back to Cusco, stopping at several attractions along the way.

First, we visited the Salinas de Maras, evaporation pools for mining salt high above the river valley. About 5,000 small pools line the hillsides like a haphazard patchwork quilt. Maintained by a cooperative of local families, the pools fill with spring-fed water that evaporates in the hot, dry sunshine. Workers gently scrape the salt from the sides and bottom of the pool and pile it in baskets to drain. Then they dam up the pool to fill again.

This article from The South China Morning Post includes a nice explanation:

Salt ponds are more commonly found on coastal plains, filled with seawater from the incoming tide. The ones in Peru are at an altitude of 3,000 metres. It’s a long way to the ocean, but it wasn’t always so; this impressive mountain range was once part the sea floor.

The movement of tectonic plates pushed the seabed up to form the Andes. The sea salt was locked into the rocks and filters out through the Qoripujio spring.

The Incas (early 13th century to 1572) are credited with many of Peru’s striking constructions, but these ponds were created during the Chanapata Culture (AD200 to AD900).

Berlin kept sticking her fingers in the spring to suck off the salty water, and I have to admit I nibbled on a few chunks of salt.

Seeing these people working in the pools gave me a new appreciation for artisan salt. The process hasn’t changed much in more than 1,000 years.

Our next stop in the Sacred Valley was Moray. Archaeologists speculate that the terraced concentric circles may have been used as an agricultural research laboratory. According to Atlas Obscura:

Studies have shown that many of the terraces contain soil that must have been imported from other parts of the region. The temperature at the top of the pits varies from that at the bottom by as much as 15ºC, creating a series of micro-climates that — not coincidentally — match many of the varied conditions across the Incan empire, leading to the conclusion that the rings were used as a test bed to see what crops could grow where.

We had planned to visit the town of Chinchero, but we were getting tired and hungry. We decided to skip it. Our driver noted that an Andean crafts market in the Chinchero District was on the way to Cusco. Did we want to stop there? Yes, please!

This friendly guy greeted us at the market.

Stella’s daughter, Mane, poses for a pano.

Inside, we found a collection of tables operated by families who have passed down their skills for generations. A friendly lady in stunning Andean clothing demonstrated the process of washing alpaca wool, spinning it into yarn, and dyeing it with natural pigments.

She also explained that a special red hue came from the cochineal, a parasitic insect. She smashed a dried cochineal between her fingers, releasing a bright red stain that she spread on her lips for long-lasting color. “You can even kiss your boyfriend!” she said. “It won’t come off!” Stella also applied a little bug-based lip stain.

I’m a sucker for textiles, and I enjoyed chatting with the families about their weaving techniques and symbolism in the finished pieces.

Tony and I bought a table runner from a husband and wife weaving team, and before we could stop them, they had placed the runner around my shoulders and put their own hats on our heads so we could pose for a photo.

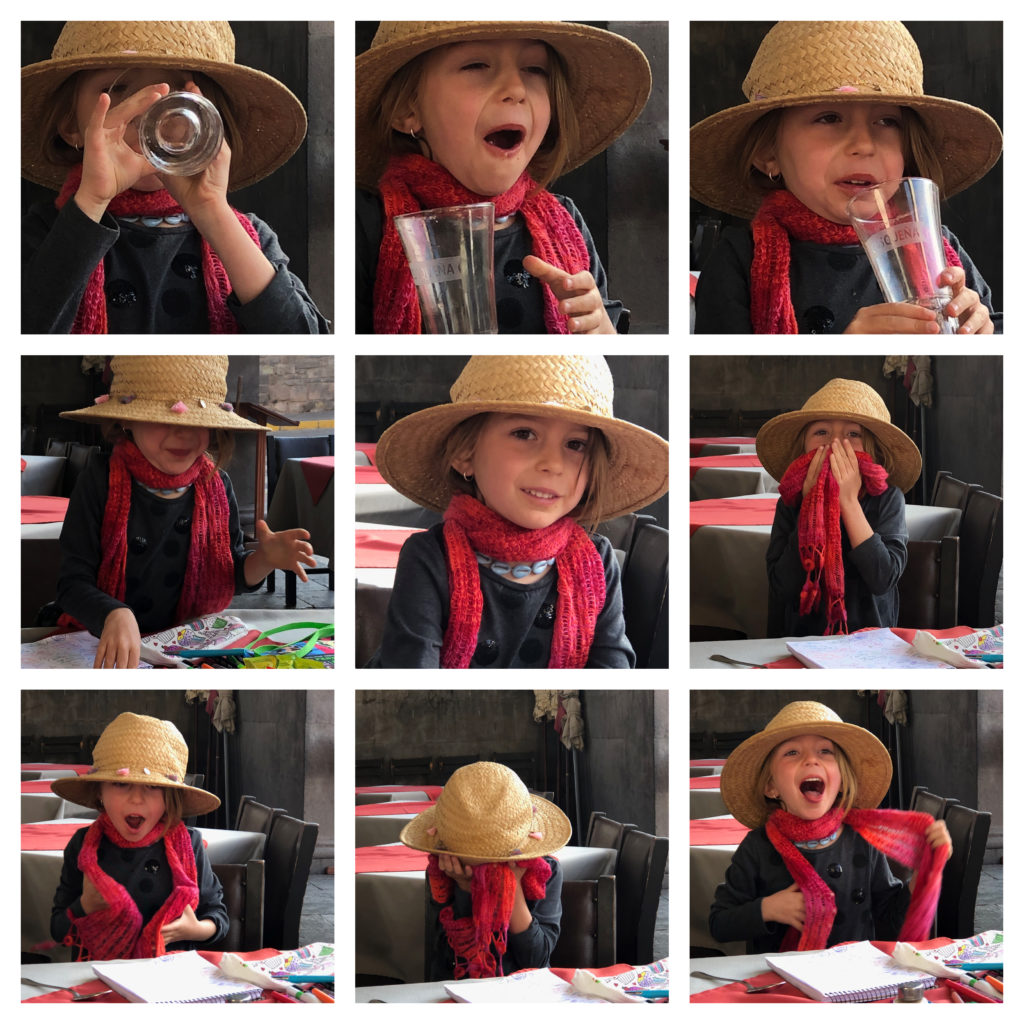

Back in Cusco, we hung out at a café beside the Plaza de Armas for awhile. Berlin wanted a taste of michelada, a blend of beer, lime, salt, hot sauce and Worcestershire sauce. That girl is such a drama queen.

That evening, Peter babysat while the rest of us enjoyed a night on the town. We found many interesting galleries and shops lining the narrow cobblestone alleys.

Our absolutely dreamy dinner at Cicciolina was the perfect ending to this Peruvian vacation, where we found fantastic food at every stop. I’m cracking up in this photo because the waiter was nearly sitting in another diner’s lap to get the shot. You can see him reflected in the mirror behind us. Hysterical!

The next morning, we flew back to Santiago, but not before customs agents flagged Ian and Peter for additional screening. Stella thought the metal skewers Peter had brought from the States might have looked suspicious, but in fact, the 12 boxes of macaroni and cheese he had brought for his grand-daughter smacked of drug smuggling. Agents busted open one of the boxes and tested the cheesy powder before finally releasing the men for the trip home.